Presentation addendum

Now, in case you didn't watch the video, the essence is that I disassembled a color cartridge for a HP1112 printer (in China, that's a HP 803 cartridge, but the type number differs per region) and took die shots to try to figure out how it works. When I couldn't find that much, I proceeded to sniff the signals between the printer and the cartridge, figured out what signals to produce to make a cartridge do my bidding, and print out lots of Nyancats and other fun stuff.

Part of this research was a lot of trial-and-error with respect to the timings of the signals. I could only guess what the relations between the signals were, so I had a pretty hard time figuring out what the order between edges should be, and what signals I could delay and which should be exactly on time. One of the reasons I looked at the silicon of the cartridge was to figure out that information. Turns out I could indeed have gotten it from putting the cartridge under a microscope, however not in the way I expected.

Before the Supercon talk, I concentrated on the color cartridges, as those seemed the most interesting. When I got home after the Supercon, I decided I also wanted to reverse engineer the black cartridge: the print head of that is wider than that of the color cartridge so I could print more at once. It probably wouldn't be that hard to add support for this cartridge as well: the pinout of the cart seemed the same, and I knew the protocol was probably alike as I already tried hooking up a black cartridge to my own hardware. Even with the software to send color images, it actually squirted out something.

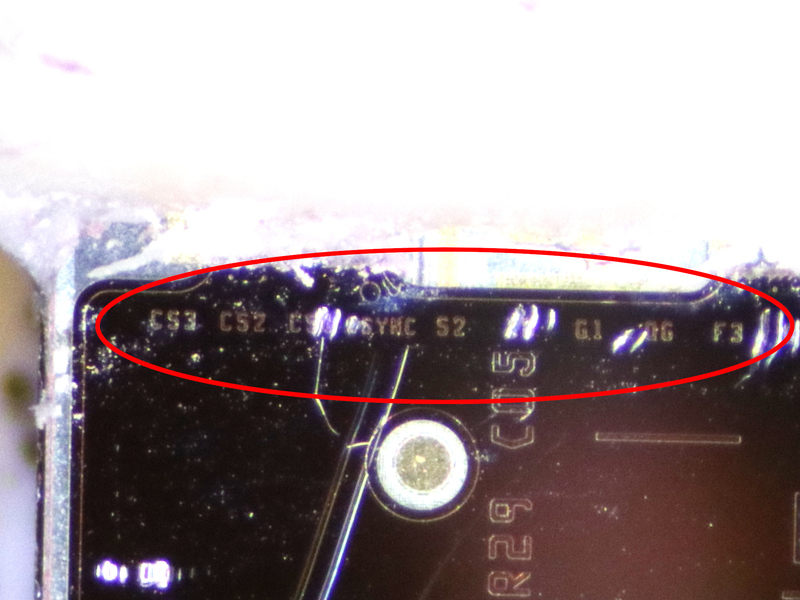

So I did what I did with the color cartridge: put it under a microscope, got rid of the silicone gunk covering the contacts, getting ready to stitch together some shots for a large-scale image. The back cartridge, however, was different from the color cartridge in that it had more writing on the metal plate with the nozzles: hidden under the silicone gunk, it had the signal names for all the pins!

(By the way, if you want to see the full microscope glory shots in full 40'ish megapixel glory, you can. Stare

at the awesomeness of the shield and silicon

of the color cartridge! Wonder at the intricacy of the nozzles and gaze at the

die shot of the black cartridge!)

While this may not sound like much, in a sea of unmarked PCBs, chips without any reference and typenumbers that lead to nothing, some actual signal names can make all the difference. On a hunch, I punched a few distinguishing signal name and the brand "Hewlett Packard" into Google Patents and out rolled the specific patent (and one older one the first referred to) for the exact technology and waveforms this cartridge used. It would have saved me so much time if I had found that while still struggling with the cartridge timings... ah well. To be fair, I can properly say that the hint was real hard to find: the signals were not only covered by silicone putty, but also miniscule: the letters are about 30µm tall, which is less than half the thickness of a human hair.

While the patent describes the inner working of the cart and is worth a read (well, given you're able to make your way through the technical legalese used) just to understand the sometimes weird logic HP uses to control all nozzles. The patent by itself is useful, but not enough to be able to control a cart; at least the majority of my reversing effort would still have been necessary even if I had this patent.

From now, I'll also use the pin and signal names that were in the patent. Note that the code may still have some of my own signal names; I'll include a translation table alongside the documentation.